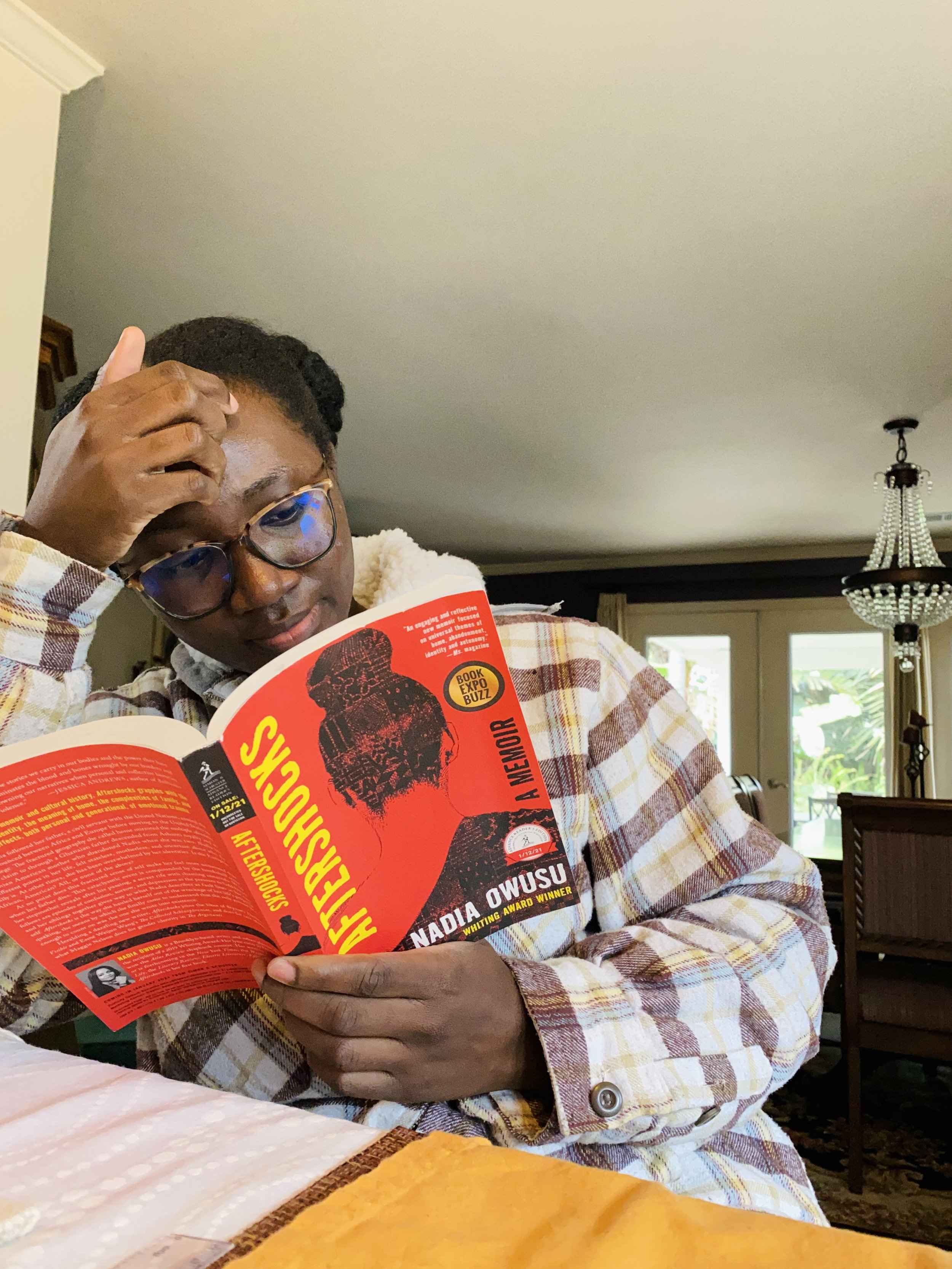

Book Review: The Heavy Work of Reckoning in Nadia Owusu’s 'Aftershocks'

The memoir begins with a curiosity and attentiveness of seven-year-old Nadia that isn’t startling, isn’t unexpected of a child but is indeed, a meaningful (albeit costly) tool that proves effective as the writer navigates a life marked by changes, motion, violence and a kind of absence that drags its weight through the years – steady and rooted.

It is what Nadia Owusu does excellently in Aftershocks: her ability to demonstrate a paradoxical relationship between the happenings in her life – a daughter’s wholesome adoration of her father clashes with a secret that is at first, both shocking and betraying; inhabiting a war-torn Ethiopia, she is at once sheltered from violence as a child of a diplomat, a privilege Owusu does not shy from acknowledging when she writes, “We swallowed guilt like the abundant seltzer we drank to spare ourselves the task of boiling bacteria out of tap water. But also, we were glad. This was not our country, not our conflict, not our calamity”; the limitedness of privilege (and the fickle nature of the concept) when back in America, her family is still black and thus, racism is a reality they cannot simply separate or shield themselves from, it is one she lives, heart in her throat as she fears for the life of her brother when he calls her from jail.

It is not surprising how much truth and revelation the book holds given all that Owusu shares. Even more ambitious is the unflinching look at herself – how she seems to open herself up with incisive prose as she interrogates her upbringing, questions her own private belief, and confronts the quality of what she has come to mold and accept as truth, one that, no matter the afflictions that orbit it, drives Owusu (as well as the reader) to the center of self, the depths and labor of one’s existence – what it means to have the capacity to love, to long for, to belong, to forgive, to forcibly come alive, despite.

The idea of roots setting a person free is counterintuitive, but deracination from the past, from land, from family, from mothers, makes for an unstable present. We must have, or we will always search for, a place to bury our bones.

Of the writer’s identity, there is what appears to be conflicting notions of belonging, almost as tumultuous as the events that take place and frame her experience of the places and people she encounters. With a Ghanaian father and an absent mother of Armenian American heritage, young Nadia was plunged deep into a world of complex identification and a separation that grips her for years. Her father’s job with the UN, while it offered her a childhood of abundance, set for her a world that was rich and unstable, promising and yet frightening, alive with presence and struck with a painful, enduring longing. A sweeping rush of settlements and adjustments, the lingering trauma of the past and the recreation of oneself to fit in the spaces that are ever changing are no doubt bound to have its consequences. For Owusu, the impact is grave, unpredictable, and a horrifying illness of the mind – a seismometer in her midbrain “that warned of fissures that would widen into deep chasms, and eventually, into an all-consuming abyss.”

The earthquake analogy is one that is heavily carried out in the memoir, a repetition that is not redundant to the work’s structure or tiring to the reader. This can be attributed to Owusu’s skillful and artistic expansion of the term as she segments her story into Foreshocks, Topography, Faults, Aftershocks, Mainshocks, Terraforming. Each chapter is preceded by a definition of the word and a note that, beyond offering further explanation, feels somewhat welcoming, a gentle nudge for anyone turning the pages, a subtle hint of what is to come. Such that even as the writer explores her descent into madness, years of damage reverberating through her life, the reader is carefully ushered towards the rumble, the tremors lying in wait. In this manner, the narrative unfolds at a thoughtful pace that is unrushed and with each detail, establishes Owusu’s voice as one that is unintimidated, critical and urgently honest.

When our stories require us to pass judgement, to inflict shame on ourselves and others, to set ourselves apart, we cause harm. Bigot, prig, the voice in my head calls me. And, I must answer honestly. I must answer yes. I want to make it not so. I have work to do on myself. I need a new story.

Aftershocks is the heavy work of reckoning that paves way and makes this newness possible. Toward this hopeful invention, Owusu’s endeavor is without performance or the slightest hint to impress but only evidently, to seek, to reconstruct and to transform. I keep thinking about James Baldwin's words: In order to have a conversation with someone, you must reveal yourself. Aftershocks, to me, has precisely the quality and texture of this kind of conversation—open, vulnerable, and audacious. I almost want to believe that when Nadia Owusu writes, “They do not recognize me as one of their own,” the haunting reality is that the misrecognition and apparent lack of belonging begins not with them but in herself. To explore the self – its disheartening tendencies, faults, and intimate obsessions – the way she has in her memoir is significant and extraordinary.